By Shifu Hayashi Tomio

This story recounts a series of events that took place over a ten-year span from early 1970 to early 1980. It is not my intent to disparage anyone in this tale but rather to candidly portray the interplay of light and shadow in the soul. The main character of my story referred to himself as the ‘Gutter Ronin.’ I will refer to him at times as GR.

I didn’t know what to expect that evening when I walked out the back door of the dance studio into the darkened parking lot in 1976. I had been teaching an adult martial art class there once a week when someone told me that GR was waiting for me outside. I recognized him immediately. He was sprawled on the hood of a car, soaking under a light rain, laughing with sardonic pleasure.

As men we were worlds apart. Even though we had trained closely for years as senior instructors for a large suburban karate dojo, I had quit in frustration a year earlier. The rare times I saw GR he appeared cagey and agitated, as if swatting some monstrous shadow. My spotty encounters with him after I left the dojo reminded me why I sought a community of the clear-headed. Nevertheless, we remained bound by our martial brotherhood.

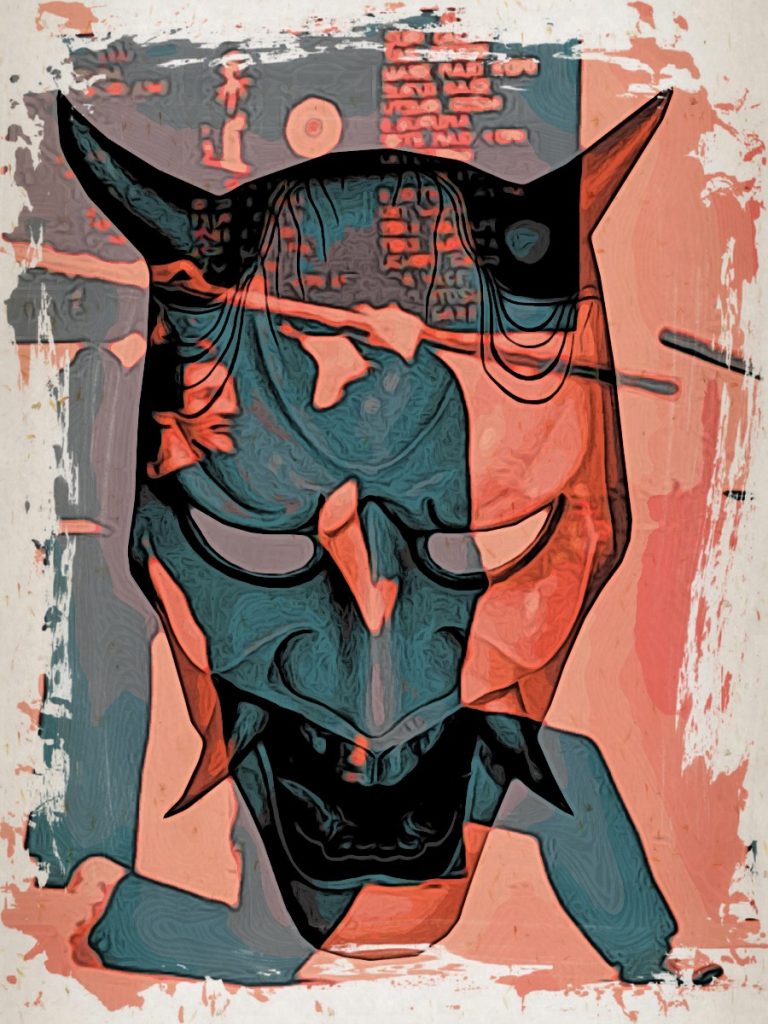

“I am a gutter ronin,” he uttered, spread eagle on the red hood.” His self-deprecating description conjured an image of a demented samurai wrecked from some long-ago lost battle. GR had become a macabre Caucasian version of Jackie Chan playing the drunken monkey fool. Only Chan was an actor. GR was the real deal. I had a morbid curiosity about his future, because I understood some of what he had gone through. I had narrowly escaped the same clutch, which held him tightly in its talons. Our sensei was a charismatic, clever, power-hungry manipulator who just happened to be an exceptional and inspiring teacher. He preyed on our innocence, and the expectation we would keep him high on his martial pedestal. It could have been me splayed on that hood. Decades later, I learned I had been nicknamed the “Sane One” by the judoka gracing the dojo before the karate classes shooed them out of the building. I guess some innate karma saved me to bear witness to the decay of human virtue. GR was just a twenty-something man on the wrong side of the street. His martial path, begun innocently enough, had slowly twisted into a dark, dispirited maze.

GR had become a small-time legend of a fading Karate school, self-crucifying in the wake of his forgotten grandeur. Perhaps, if he had been nailed onto his metallic altar that night he would have garnered more compassion. But no one came to pierce his side and relieve his suffering. They came instead to watch a circus performance from a man who foolishly boasted he would tackle any opponent. His once clear mind had fractured, robbing him of that crucial victory over self that could have led him to a peaceful future. This night, his muddied thoughts overwhelmed any campaign toward clarity, disassociating him from his wounded spirit.

It was only later that I discovered GR had sustained himself on a mixture of Stelazine, cocaine, and alcohol that night. The Stelazine tranquilized his hands from turning into fists at inappropriate times. I was told that his self-administered cocktails didn’t slow his nightly forays into Newark’s rough bars to flirt with danger. At Gary’s Go-Go, he’d cautiously bump patrons who might be armed to minimize his disadvantage in a confrontation.

GR went through three years of psychotherapy to relieve the imbalances of his karate training and martial relationships. His story gives testimony to the darker side of the martial arts. Instead of building a man, his sensei let the art tear him apart. And if his sensei wasn’t directly guilty of this immoral crime, he allowed a young man’s degeneration to unfold without compassion. As my college professor once reiterated, ‘power corrupts and more power corrupts more,’ I have witnessed the martial arts become a destructive opiate for some men’s egos. With the black belt cinched around their waist, some begin to falsely believe their superiority over others. Maybe the alcohol and cocaine had blanketed the Gutter Ronin’s inner rage and tempered his power surges. GR’s volcanic spirit spewed out fantastic images.

“We’re moving in opposite directions,” I told him that night.

“I know. I’m in a dark pit, clawing my way into the darkness,” he said with bravado, egging his demons to brawl. He was oddly detached from his fall from grace. Maybe he was just clever at masking the terror of his plummet. I thought he was searching for life meaning in a tar pit.

Despite GR’s wildness, he was an excellent martial artist in his day. We marveled at his kicking strength. Even holding eight-inch-thick pads, the biggest men in the dojo would be knocked completely off their feet with his back kicks.

Both bitten hard by the martial bug, we had trained and taught side by side for years, pacing ourselves to each other’s progress. I was introduced to him in the early 1970’s by the sound of his makiwara pounding. Makiwara work was a bone deep addiction with GR in the early days.

Our youthful minds felt limitless. Being strong and full of ambition we rose to sensei status. This is where we stumbled, for love is often blind regardless of the object of its attention. Karate’s romantic and alluring charm engaged us so fully that we completely overlooked our teacher’s alcoholic binges and his exploiting of our labor.

Controversy surrounded the years that followed. My dojo experiences gradually soured. I quit my position as senior staff instructor with some illusions shattered. GR hung on three more years. I never saw or spoke to him again until the dojo mysteriously burned in the summer of 1982. I heard the news from the uncle of a young student whom I had been teaching. “There’s a karate school on fire the next town over,” he told me.

As soon my class ended, I drove to Main Street, Summit. I arrived to find the entire block cordoned by police and fire equipment. The pioneering Bank Street Dojo had been smoldering for hours. As I sought a better vantage, I recognized several former students standing behind the fire lines. How many had come to pay homage to our unique, old world training hall?

I strove for different angles on the street, as if each might yield a clue to its demise. Sometime later, I heard that the Fire Marshall had ruled the fire “suspicious.” Prevented from circumventing the structure, I shortcut down a wide back alley when I got the distinct sensation I was being followed. I stepped over to a small crowd and focused my attention on the alley entrance from which I had just emerged. The Gutter Ronin stepped from the alley into full view. He hadn’t changed at all. He walked like an intelligent animal who carried a lethal left hook and right round kick as a surprise. He stood six two. His solid, near two-hundred pound frame supported a confident, lithe body, with a Jack Nicholson grin.

GR respected me as a man and a martial artist. I respected his lethality. We walked around the corner to a local watering hole to exchange thoughts about the dojo’s dark turn of events.

Our former sensei had coincidentally left town the day before. We agreed that given the debasement of the school, fire was a fitting end.

From time to time, I would reflect how GR and I had chosen different courses for our lives, yet always strongly maintained our one common denominator, karate, in high regard. We both suffered as youths from the same misconception that men are inherently good, and that the martial art sensei, like a priest or a cop to a child, must be steps above the good man. It’s what we wanted to believe. The truth however, roamed in another pasture. Some cops are criminal. Some priests prey on young children. When I told the Gutter Ronin that a class action suit was underway against our former teacher for defrauding members, he asked who in their right mind would pursue the devil, “the fat devil,” he called him. Only GR dared to call him that. He had lived with the man for years, enduring threats and drunken rows, chauffeuring him after late night binges. Our beloved sensei had long ago fallen for the bottle. “Now…,” GR remarked, “he must be secluded in some lair waiting for his next victim to make the same mistakes.” I think GR was referring to the common errors of youth – the belief that innocent trust will surely guide one harmlessly through life’s death-defying maze.

It should be noted that many people had excellent martial experiences at our dojo and a favorable relationship with the entire teaching staff. But the events behind closed doors revealed a more shadowy narrative.

GR was a colorful and energetic man. No matter what you said to him, good or bad, he’d grin broadly and laugh infectiously. He loved an audience. With spectators he became the spectacle, the grand patriarch of combat prowess. “The great water hippo… the Gutter Ronin.” He lavished these fantastical titles upon himself. I truly think that GR believed his spirit had been unscathed, that he could outfox the foxes who had torn off his sinewy wings to freedom. GR was brilliant, yet darkly wild. As a martial brother I wanted to believe that he would escape his tormentors, knowing in my heart his chains were thick.

I heard that GR had gotten into a fight at a local Inn several towns over. Angry men cut deep with the force of their karate technique. He smashed the man’s face, crushed his upper bridge, drove four of his top teeth and several of the lower into the back of his mouth. That mouth will be indelibly marked with a porcelain and metal plaque of the night’s incident.

GR recounted that the man had emerged from the rest room and saw him dancing with his woman. Overcome with the machismo that runs hot at bars, the stranger shoved him from behind, then spun him around. GR was a technical beast. He rooted in mid-pirouette. He had trained relentlessly for the fight. He reacted without hesitation, caught the intruder with a solid right hook to his cheekbone followed by a left that he described as “sizzling.” If any man should lay violent hands upon GR there would be no verbal negotiation, no pumping of chests. I remember the day when a testy student suggested to GR that if he had lived in the Wild West, he’d call him out for a draw. GR replied, “I’d gun you down in mid-sentence.” That’s how the Gutter Ronin thought. Hit first, then get on with your life. So it was that night as his two strikes cracked the man’s face open. He told me the stranger didn’t buckle, didn’t jolt. His eyes never dilated. The inside of his mouth simply exploded. How could this poor suburbanite have known that he had just stepped on the tail of an angry man-beast?

The Gutter Ronin recounted this story to an audience of two novice students I had brought him months after the fire. We had squeezed into a booth at a local restaurant. I wanted to rock the innocence of my young male disciples, about the ugliness of real combat.

The senior most of the two was visibly nervous. He’d heard my many tales of the wild man’s instinct for the kill. He listened intently, occasionally glancing at me to measure my response to GR’s gushing. What does a young, twenty-year old think when he stares at the Gutter Ronin’s huge calloused hands and broad, bull-thick forehead? GR used the conversation to shadow box an unseen enemy. “Did he tell you about high impact strikes? Don’t ever hit the mouth with your fist … I had this fight with this guy at the plant. He tried to shake me down for money, ran his boot along my car, slapped me in the face. I wiped away his second slap, caught him with a hook. I wanted to hit his arm but my punch bounced into his ribs. Your instructor, he fights in a completely different style, strictly by the book. He wants a clean kill. Me, I’m liable to roll around on the ground with my opponent, let him drag me by the hair through the mud if he wants, before I finish him off…” He guffaws at his fantasies.

GR’s fights were real. But they were physical victories. I never saw him wage the decisive inner battle. Seven years and a lot of anxiety later GR realized that he had been manipulated and abused by his teacher.

GR is a living testimony to the brutality of man’s lust for the fight, man’s struggle to find himself through blood and glory. I don’t know if GR ever gained any ground in his mortal combat for balance. Sadly, there were rumors he struggled with a mental illness, paranoid schizophrenia, that emerged during his prime years in karate.

The two students left us alone for a moment. GR asked me, “How good are they?” He was surprised when I told him the brown belt had six years of training, the other only studying for three months.

“Your brown belt’s scared,” GR said. “I see it in his eyes.”

“You’re right,” I agreed with his keen assessment. “He’s psychologically inhibited. He’s got superb technique, but he holds himself back.”

“That’s half the battle,” the Gutter Ronin added. “That brown belt wouldn’t last one nanosecond with me. The other, he’s got something.” GR paused. “I’d give him two nanoseconds.” His deep belly laugh filled the room, erupting from the pride in his own fiery wit.

…

The Dojo permanently shuttered after that fire. Its head instructor disappeared for years. He died of cancer at age 54 in 2000. GR also dropped from the karate world. None of us saw or heard from him again until a former dojo member discovered his obituary. The brown belt who met the gutter Ronin that day, thirty years ago, went on to become a sensei himself. He split from my teaching and opened his own karate school. He died in a tragic car crash in his 50’s. I heard through the grapevine this his long-term bouts with his own shadows had enveloped him. The interplay of light, shadow, and darkness dances through our lives. Life moves on when and where it can.