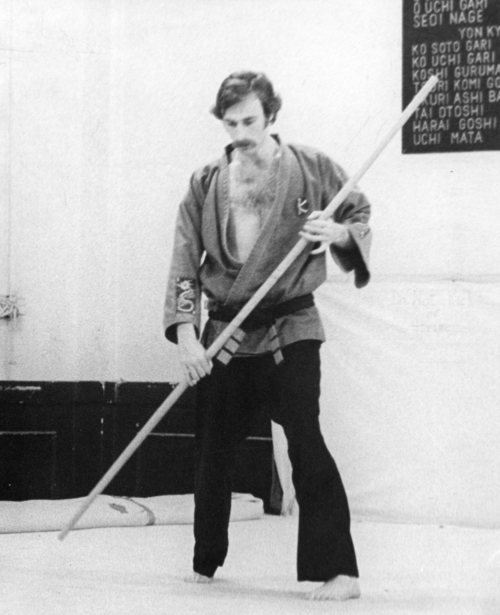

(Early 1970’s, Bank Street Dojo, photo of Shifu Goedecke)

Further Thoughts on Kata and Bunkai

Chris Goedecke, 2014

(Shifu Hayashi adds to Professor Robert Arnold’s earlier post):

In the general is concealed the specific. In the specific is concealed the general. We are only limited in any moment by our fixations on the general or the specific.

It is well established amongst the kata/form orthodoxy that the true form is ‘no form’, a fluid, non-attached, yet principled expression of movement, unhindered, unimpeded by any ego constraints.

Okinawan, Naha-te kata were altered to meet the bodyguard needs of the Shuri castle. Shuri-te katas were modified by the next generation of masters to meet evolving civilian needs. Ankou Itosu, Shorin ryu’s karate founder, taught kata but never taught its bunkai. Subsequently, the once, world popular, Shotokan style had to interpret their kata anew.

Early Okinawan karate practitioners were baffled by Sanchin kata, so much so, they closed its original, open-handed moves to make more sense out of it as a fisted combat form. Their difficulty stemmed from the fact that the form was originally a sai kata, but no one told them that.

There is plenty of documentation out there if you want to dig it up, that some masters taught kata then asked their students to figure it out, while others taught multiple tiers of interpretations, beginning with basic block/hit moves, followed by ‘hidden grappling techniques,’ advanced pressure point strikes, or energy manipulations. In certain styles of Tai Chi, masters from the south debate those from the north over the most subtle of nuances for the same move. The black and white of our arts conceals many shades of gray.

I would hazard a guess that many martial artists may not even be aware that there are specific inner formulas involving visualizations, precise breathing patterns, and mental settings that remarkably enhance a kata’s surface movements. In very high-level performance it is understood that without those variables, one is only performing a ‘half-kata’.

What emerges from the history of kata’s evolution then, is a panoramic perspective. Each form has its own value system, neither in opposition, nor collusion with another’s kata vantage. We could divide this panorama into two equally, valid sections. One side viewing kata as a general template, in which the student makes malleable the form to suit the task, whether it be practical, therapeutic or meditative. Then there is the other side— a kata fixed with specific purpose upon which no new information can be added (with the exception of slight modifications for height, distance, strength, and timing).

I personally embrace both sides to create the full face of kata.

As to the latter perspective, I would like to credit the value of such forms for their technical depth within the context of the application. What I think is being stated is that the masters worked out the technical solution to the near nth degree in the manner in which the hands, feet, and torso should be placed or moved to maximize the bunkai’s effect. But even in the act of achieving this finitness, a student must go through many gradations of fine motor controls to make it work effortlessly.

As to the general template of kata, it offers the foundation for creative problem solving. In my own teaching, I find it an invaluable experience for the student to eventually think for himself and recognize that even when a situation and given bunkai appear ideal, things can easily go awry. The new solution will often require a freer set of skills not be so simply imparted if one must adhere strictly to set responses.