Seisan (also Seishan or Sesan) is one of the most widely practiced forms in traditional Okinawan karate. Prior to 1908, according to one researcher, every major style taught it. Its origins are steeped in both history and legend.

Historians have found no evidence suggesting Seshan was a Chinese master credited with the Kata’s origins. Even the exact date of its creation has not been pinpointed, but guesstimated at somewhere between the 17th and early 19th century. It is generally accepted that the form originated in Southern China where elements of it can be found in several boxing methods (Tiger, Lion and Monk style). Some believe it derives from the Yong Chun White Crane (Yong Chun) or Monk Fist (Luohan Quan) systems from Fujian Province in Southern China. Trade and cultural exchanges between China and Okinawa likely included martial arts in the 17th–19th centuries.

“Seisan” (十三) translates as “thirteen” in Japanese. Historians have cited numerous reasons for the Kata’s numeric labeling, the more prominent being: “13 techniques”, (only if a different technique is counted once in the form); also, “Three Fronts,” due to the repetitious nature of movement patterns in sets of three; Seisan-Bo, for the belief it was a form practiced in the 13th of 36 chambers in the Shaolin temple; “13 directions” preferred by U.S. master, J.A. Advincula, who combines actions with actual directions to arrive at 13. Lastly, there is the Sanskrit interpretation by the late Nagaboshi Tomio, ‘Born of the Three’, which I adhere to when internal principles are brought into the equation.

Perhaps, the early masters were more concerned with preserving a kata’s physical transmission than documenting its history or philosophy. Yet, for a form as deeply embedded in the DNA of Okinawan karate history, the absence of a clearly recorded reason for the name “13” is striking, especially given how central numbers can be in both martial and esoteric traditions. This gap might exist because early karate was transmitted orally and through practice, not formalized in writing. Its practitioners also might not have questioned or preserved the reason behind it.

Cross-Cultural Layers

In Chinese martial arts, numbers often have layered symbolic, spiritual or tactical meanings. When transmitted across cultures, the original rationale behind “13” could have easily been altered both in translation and understanding.

Let’s look at some possibilities for the numeric labeling; 13 may refer to techniques: 13 steps, 13 attacks, 13 directions, or a symbolic number associated with luck or esoteric meanings in Chinese numerology. Seisan may have signified 13 core principles or postures, 13 symbolic energies or fighting methods, a coded reference to a Buddhist (13 Hands of Buddha, a concept in Chinese Buddhism) or Taoist teachings, adding a metaphysical layer to the Kata’s legacy. “13” could have been a categorical tool, such as the date Seisan was created, a lineage marker or position in a curriculum or an organizational designation i.e., 13th in a series or contextual to a specific time/place, i.e., a temple, or a Chinese naming convention, like saying “This is the thirteenth form in a larger system,” or “This form was taught on the thirteenth day/level/house.”

Okinawan and Chinese masters were known to intentionally veil deeper teachings by using metaphor or poetic names or numbers to preserve secrecy, or to reserve certain knowledge for their most advanced students. If we had a written legacy from someone like Gojuryu’s, Kanryo Higaonna, or his teachers, this might be clearer.

The nature of an art forged through war, migration, secrecy, and oral lineage could also suggest intentional obscurity. Logic suggests if the number 13 held deep significance to the function or internal logic of Seisan, it’s meaning would have likely been preserved and passed master-to-disciple with more clarity.

It’s also worth noting the Okinawan masters often renamed or adapted a kata to personalize it. The “Seisan” label could have been applied after the fact, perhaps retrofitting a Chinese form into an evolving Okinawan system where it was given a numbered name for cataloging something other than insight. The nuances and distinct movement differences in its many variations only adds further confusion. While modern practitioners might hope to find hidden combative truths in the enigmatic 13, it’s likely the essence of Seisan lies more in the kata’s structure, rhythm, and internal mechanics, not its name.

Seisan is a foundational kata in the Naha-te branch of Okinawan karate, which includes Gojuryu, Shitoryu, Uechiryu, and other less well-known systems. These systems emphasize breathing, rooted stances, and circular hand techniques, all present in Seisan.

One of the earliest records of Seisan in Okinawa appears in the teachings of Kanryo Higaonna (1853–1915), a pivotal figure in Okinawan karate who trained in China (especially in Fuzhou) and brought back multiple katas, including Seisan. Some oral traditions claim Seisan predates Higaonna and was practiced in Okinawa as early as the 1700s, passed down in different villages and families.

Several versions of Seisan exist, varying in the number and direction of steps. Some emphasize hard vs. soft techniques, different breathing patterns, and tension-release principles. For example, Gojuryu Seisan is rooted and powerful with Sanchin-like tension elements, while Shitoryu Seisan is more linear and stylized. Uechiryu Seisan shows a stronger Chinese influence.

Purpose and Strategy

Seisan is considered by some a mid-level kata, others, an advanced form, teaching transitions between hard and soft techniques, multi-angle defense, close-range combat and tactics against multiple opponents and see it bridging foundational breathing forms like Sanchin to more combative and/or complex kata.

Let’s look at Seisan kata through the lens of combative strategy, and focus on what its structure, transitions, and rhythm actually teach, regardless of the name.

Seisan Kata: Combative Breakdown

Seisan Kata: Combative Breakdown

Centerline Domination through Forward Pressure

The kata emphasizes advancing steps, particularly with strong linear strikes and knife-hand traps and blocks. This teaches overwhelming pressure, seizing the initiative before the opponent can set their base.

Combat Insight

Strike first, dominate the centerline, and close distance fast, useful in close-quarters or street combat.

Off-Angle Movement (Tai Sabaki)

Seisan contains calculated angling, especially in its transitions into 90 degree turns while maintaining a rooted base.

Combat Insight

Evade direct attacks while redirecting force. This creates openings and unbalances the opponent.

Rooted Power (Stance Shifting)

The kata alternates between Sanchin or Seisan-dachi (rooted) and Shiko-dachi (open power stance), reinforces a stable base during offense and ground transfer during throws or joint manipulation.

Combat Insight

Power comes from the earth. Transitions teach how to deliver force without sacrificing balance.

Push-Pull Energy (Yin/Yang Tactics)

The Form’s contrasts between explosive moves and soft, circular movements (like sweeping mid and low parries). Some versions mix open and closed hand techniques emphasizing soft/hard transitions.

Combat Insight

Control your opponent not just with strength, but with redirection, sensitivity, and energy manipulation.

Close-Quarter Techniques (Elbows, Grabs, Traps)

Many interpretations of Seisan reveal elbow strikes, palm pushes, arm traps or grabs before counter hits.

Combat Insight

Seisan assumes you’re already close, ideal for real fights, not sport. It teaches how to survive in tight quarters.

Dual Engagement (Multiple Opponents)

Some believe Seisan’s turns and strikes suggest multiple opponents, especially when turning suddenly with a block-strike combination.

Combat Insight:

Training awareness for ambushes, flanks, or unpredictable movement — not a one-on-one dojo duel.

Breath and Tension Control

In the Gojuryu and Naha-te versions, breath control and tension-release cycles are integral. Coordinated inhales absorb and exhales accentuate strike or stabilize.

Combat Insight

Mastering internal timing, energy compression, explosive release and Ki as tactical breathwork

Seisan’s structure reveals strategic, battle-tested logic: Enter fast—Disrupt balance—Redirect force—Control your breath–Root but remain mobile—Adapt to chaos. Seisan lays the foundation for intelligent, in-close survival tactics.

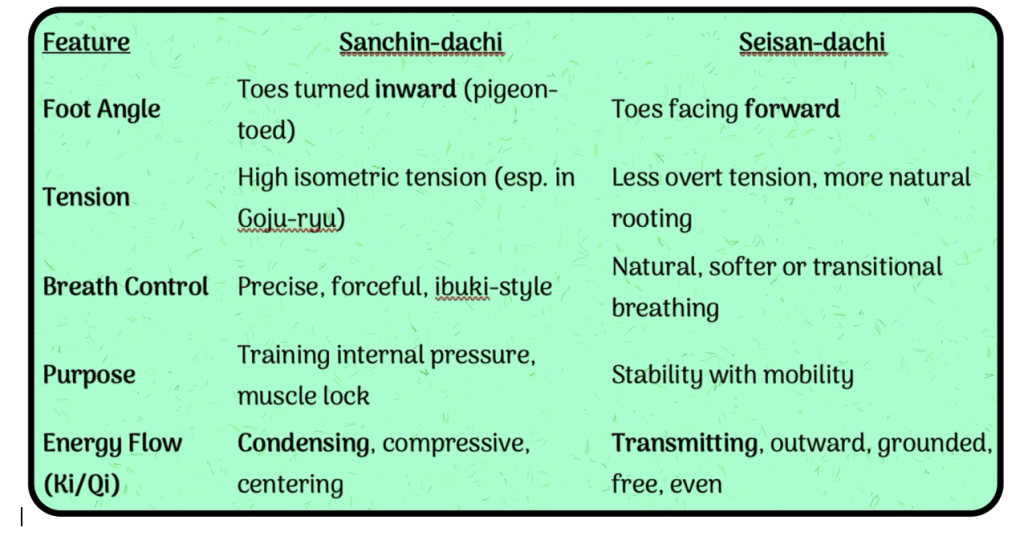

While some schools use Sanchin-dachi in the Form, the traditional stance used in most variants is Seisan-dachi. These are subtly, but critically, different posture in terms of both biomechanics and internal energy flow. The feet turned inward versus straight creates a nuanced Ki flow quality.

Sanchin-dachi cultivates inward gathering of Ki by rooting energy toward the center (dantien). It reinforces internal structure, static integrity, and breath/body synchronization. Seisan-dachi, on the other hand, is more conducive to energy projection and mobility. The stance is more open and dynamic, allowing Ki to flow through the limbs and spine. This facilitates rapid transitions, directional shifts, and explosive power. Seisan emphasizes the use of forward-facing feet while other kata’s stress inward (neihanchi) or outward (shiko-dachi) rotated foot positions.

Function in Seisan Kata

By using Seisan-dachi, the form subtly emphasizes forward pressure with readiness to pivot or shift, structural integrity without locking the hips, natural breath movement — ideal for flow and explosive release, and an internal strategy of readiness and projection, rather than containment and refinement (as in Sanchin-dachi).

While the visual distinction between these stances appears small to the untrained eye, their energetic intent is very different which impacts how techniques are delivered, absorbed, and transitioned.

The choice of stance in a kata reflects not just tactical positioning, but how Ki is channeled and released.

In some cases, we see schools coupling breathing patterns with different stances. However, this is a mistaken understanding of how breath works with stance to enhance technique. For example, while ibuki breathing may be coupled with Sanchin dachi and not Seisan dachi, it need not be this way. One can also practice slow, abdominal breathing with a Sanchin dachi creating a different, but no less valuable outcome. This vital refinement cuts through many of the rigid pairings that have crept over time into karate’s pedagogy. I am highlighting something that experienced internal practitioners understand deeply.

Technical quality emerges not from stance or breath alone, but from how they integrate. This integration can take on many valid forms.

While many schools have created standardized pairings such as ibuki breath with Sanchin-dachi or natural abdominal breath with Seisan-dachi, these are training conventions, not laws of biomechanics or energy. A Sanchin-dachi can be explored with soft, natural breathing to cultivate grounded awareness, tension-free rootedness, the overall effects of micro-adjustments through the fascia, subtle energy flows in the limbs. Similarly, one could apply sharp exhalations or controlled bursts in Seisan-dachi to amplify explosive movement, heighten the momentary structure or direct Ki outward along kinetic chains.

When you vary your breath in any stance, you’re adjusting energy directionality (inward vs. outward), muscle recruitment patterns, nervous system tone (sympathetic vs. parasympathetic activation), timing and rhythm of the technique. The same physical stance say, Sanchin-dachi, becomes a different vehicle depending on whether you’re holding tension with a compressed breath (hard-style), relaxed with slow breathing (neigong-like), or cycling the breath rhythmically with movement (qigong-style)

I advocate a non-dogmatic, exploratory approach to karate’s three pillars: kata, kumite and kihon. Rather than pairing a certain stance or technique with a fixed breath model, advanced practitioners should be asking: What am I cultivating here? Structure? Softness? Explosiveness? Awareness? What kind of breath supports this purpose, in this moment, through this stance? This is a critical analysis transcending style, lineage, or tradition.

Despite their profound impact on skill and performance let me offer a layered explanation of why so few martial artists are aware of internal cultivation practices, which cuts to the heart of the disconnect between outer form and inner function.

Surface Learning Has Becomes the Norm

Most modern martial arts are taught in group class settings. In such environments efficiency (i.e., learning expediency) and repetition are prioritized. Forms (kata), techniques, and drills are emphasized over introspective exploration. There’s limited time for subtle, slow, inwardly focused practices. Internal work doesn’t scale easily. It’s often invisible and non-demonstrative so it gets edged out by the visible and the repeatable.

Lineage Fragmentation and Cultural Export

Many internal methods were transmitted orally and thus reserved for close, often family-line students. Information got diluted or dropped as martial arts spread from China to Okinawa, to Japan, then to the West. Nuances were intentionally omitted when arts were repackaged for children, military, or sport contexts. What remained was often the “chassis” that is, the form and function, without the “engine” of breath, intent, fascia, and mind-body integration.

Internal Skills Require a Different Kind of Mind

Internal cultivation needs introspective awareness—patience with ambiguity—willingness to feel into your body and stay with sensation. But many modern martial artists are drawn to the external markers of success (speed, strength, rank, medals) They lack a framework to explore what’s not visible or quantifiable. Without mentorship, internal skills can feel “unreal” until one meets someone who has them.

Internal Skills Take Longer and Don’t Look Flashy

Most people want fast results. Most (but not all) internal methods can take years before yielding visible power. They often require undoing tension, retraining breath, and cultivating subtleties that aren’t showy. In comparison, external techniques give immediate performance feedback and a clear sense of progress (strikes land harder, moves get cleaner). Internal work is often abandoned because it seems slow, unclear, or “woo” until one feels what it can do.

The Internal Path Is Often Triggered by Crisis

Many advanced martial artists don’t explore internal training until they either suffer injury, forcing them to train differently, plateau and stop improving, or they meet someone who outclasses them with “no force” or “effortless power”, triggering the question, What do they have that I don’t?

Internal cultivation is a hidden thread, not because it lacks value, but because it demands different eyes to see it. The internal arts require a different pedagogy, a different kind of student, and a guide who knows where the door is.

Outside of the fact that internal martial art remains out of mind of most western practitioners, is it also possible that acquiring such skills may not have been in the best interest of certain ruling factions; organizations, institutions, globalist agendas. It’s easy to drift into conspiracy here, but there’s a strong historical and psychological basis for this suspicion.

Advanced internal martial skills cultivate autonomy, sovereignty, and deep mind-body integration, all of which run counter to systems that thrive on control, dependency, and external validation. Let me unpack this from multiple angles, not as paranoid theory, but as a thoughtful examination of power, perception, and pedagogy.

Internal Arts Cultivate Personal Sovereignty

Internal training develops embodied awareness (you’re harder to manipulate), nervous system regulation (you’re less reactive to fear-based narratives), subtle energy perception (you become sensitive to truth/disruption) and non-coercive power (you’re effective without being aggressive). These are not traits that centralized systems: political, military, corporate, or religious tend to encourage.

Historical Precedent: The Suppression of Subtle Arts

Throughout history, when ruling elites felt threatened, they often banned martial arts (Okinawa’s weapons bans), regulated knowledge transmission (Tokugawa era in Japan) or absorbed or co-opted schools into nationalistic or institutional frameworks. Why? Because advanced internal skills create people who can’t be easily dominated. They forge warriors who don’t need external authority to act justly. They enable resistance without visible weapons. Internal power is invisible, quiet, and hard to detect — making it both threatening and uncontainable.

Modern Institutions Favor Performance over Depth

Martial arts in the modern West are often channeled through Sport organizations (Olympics, tournaments), Children’s programs (belts, ranks, discipline)

Military/police applications (control, efficiency). All of these favor external performance metrics, fast-track, scalable teaching and rule-based hierarchy

The internal dimension, which requires slowing down, going inward, and trusting personal experience is inconvenient in such models. It doesn’t monetize well. It doesn’t rank well. It doesn’t obey hierarchy well.

Global Agendas and the Homogenization of Culture

In a globalized world, there’s an accelerating push for standardization of knowledge, efficiency and uniformity, and external credentialing. Internal martial arts are non-standard and deeply personal. They emerge from deep traditions that resist homogenization. They encourage people to become sovereign actors, not passive consumers. The globalist lens doesn’t necessarily suppress internal arts but it ignores them, because they can’t be scaled, sold, or easily measured.

Suppression or Neglect?

Likely both. Neglect by institutions because the internal path is perceived as inefficient, unmeasurable, and hard to commodify, and suppression, intentional or not, by those who benefit when people remain externally focused, stressed, reactive, and disembodied.

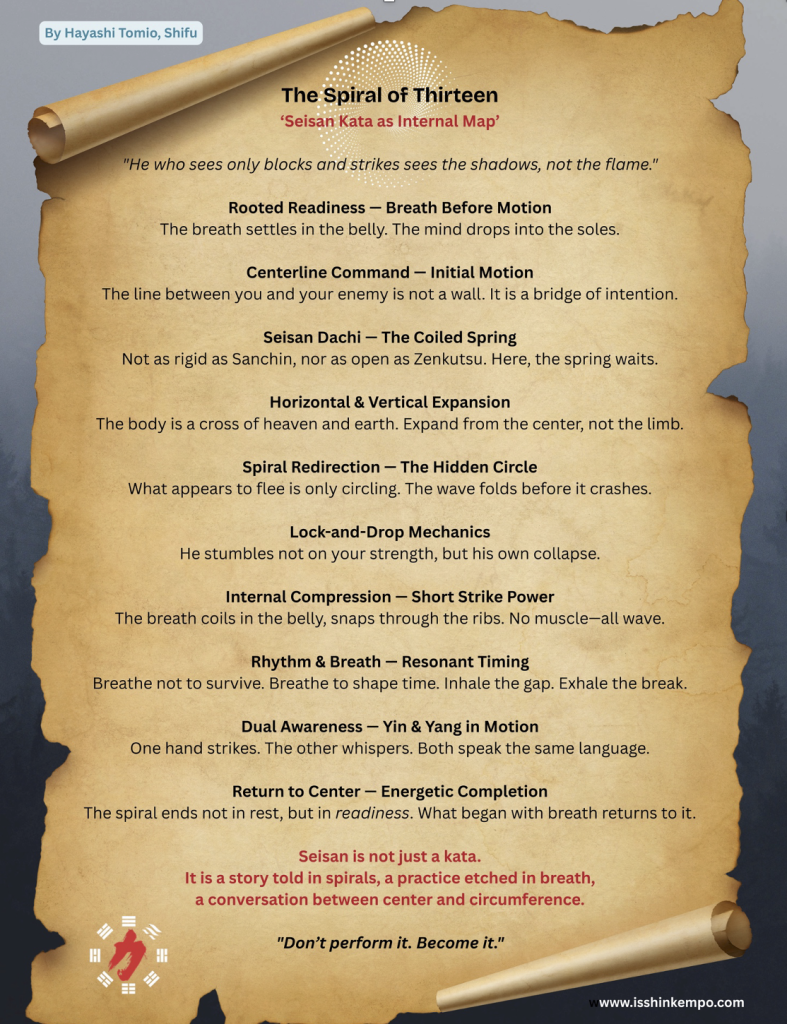

What may appear externally as a retreat or turn often conceals an internal redirection or energetic pivot, one that sets up off-balancing, redirection, takedown, joint manipulation or Ki management. These aren’t inefficiencies, though such actions can seem counter-intuitive. They are subtle spirals of control. In my experience, the deeper layers of kata, like Seisan, are often overlooked or misinterpreted. Here’s a combative breakdown of Seisan integrating the interplay between internal redirection, subtle energy flow, and external combative form.

Seisan Kata: Combative Breakdown with Internal Dynamics

Rooted Readiness (Opening Posture)

The opening stance establishes breath control, presence, and spatial awareness.

Externally, it is a preparation. Internally it is a gathering of Ki, signaling the transition from stillness to spiraling force.

Central Line Integrity (Initial Strikes & Blocks)

Rapid forward motion with blocks and strikes targets the opponent’s centerline.

Externally, this is offensive or defensive action. Internally, this is a projection of intention through the dantien, aligning breath, hip rotation and ki-pumping limb action.

Seisan Dachi – The Coiled Spring Stance

The straight-footed Seisan dachi supports flexible rootedness. Allows breath to settle into the lower abdomen, supporting soft/firm energy transitions.

Vertical & Horizontal Expansion

Upward and lower blocks paired with middle strikes represent expansion of energy in multiple planes. Internal cue: Crown-to-tail elongation while driving force through elbows and hips.

Spiraling Redirection (Internal Tactics)

Certain turns or retreats in Seisan are not just designed for multiple opponents, but rather to unseat or unbalance a single opponent through energetic redirection. What seems counterintuitive externally, such as stepping away or turning one’s back, can actually be internally coherent when seen as redirecting the opponent’s force into emptiness, setting up a take downs, limb entrapment or spiraling joint lock or aligning the spine with subtle Ki flow transitions and moving the center in ways that unroot or off balance the attacker while preserving one’s own balance. Redirecting Ki spirals inward, or outward, syncing breath with circular motion.

In this context, Seisan reveals a nonlinear combat logic, one not predicated on dominance or force, but on timing, intention, and subtle repositioning. It’s as if the kata is choreographing how to “disappear” from the opponent’s power structure and re-emerge with control.

Lock-and-Drop Mechanics (Hidden in Angled Stepping)

Diagonal or backward steps used to trap limbs or redirect the center of mass may appear defensive but hide aggressive structural disruption (i.e., a hidden tai-sabaki or leg sweep). Breath stabilizes the spine while the hips rotate independently opening a vertical channel for inner power release.

Explosive Ki Compression (Short-Range Techniques)

Quick, tight actions are not solely for striking or blocking but coiling and releasing internal pressure. Muscular tension is minimal; instead, the focus is on intra-abdominal compression and spine wave.

Resonant Timing (Kime Through Breath and Pause)

Breath is not just matched to movement. It creates rhythmic modulation that conceals or reveals intent. Ki flows more efficiently when the inhale gathers and the exhale releases through spiraling motion.

Dual-Wielded Awareness (Striking & Blocking Simultaneously)

Movements like double blocks, high-low combos, or chambered backfists serve dual purposes. They control one limb while damaging or off-balancing with the other. Internally, they split attention, yin-yang awareness, the body moving in two energetic directions.

Reasserting The Center

The closing movements of Seisan aren’t merely ritual. They return the practitioner to center, consolidating energetic pathways. Internally, the breath slows, Ki returns to pool in the lower dantien. The “gate of the spine” (mingmen) retains.